Web Writing and Citation: The Authority of Communities

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 2 The web is made of citations. Without citations, instead of a web, there would be a worldwide collection of unconnected digital spaces. Hypertext markup language (HTML) would just be text markup language. Despite this interweaving of the Internet and citation, the Internet has often been blamed for plagiarism. 1 Certainly students can copy and paste passages from websites and other digital documents more easily than from printed books and articles. It is true, too, that teachers can more quickly search for the sources of specific passages they suspect of having been plagiarized. Taking an arms race approach to the web and plagiarism, however, makes instructors into enforcers rather than educators. 2 More to the point, the communities and cultures that come together online tend to value citation, even if they do not value copyright and its legalities. Downloading a movie is fine; claiming to have made it is not.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 2 Instead of looking at the influence of the web and digital cultures as a problem to be solved, instructors should take advantage of the importance of citation in online communities to help students understand the logic behind different ways of giving credit and to see that, while footnotes may seem esoteric and academic citation formats arbitrary, they are akin to practices in which students who are active online engage on a daily basis. In other words, web writing presents an opportunity to teach citation as a community practice—and to make giving credit something students want to do, rather than something they have to do. In composition courses, this goal can be reached by studying existing web writing, producing web writing, especially when it is embedded within existing communities, and finally, through the development of a unique set of citation standards based on the authority of the class as a community.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 2 Traditional ways of teaching citation are authoritarian and follow what Paulo Freire designated as the “banking model” of education. 3 Knowledge is treated as a set quantity; citation standards are treated as unchanging ideals that must be deposited into students’ minds. Teaching citation through observation of and participation in online communities, by contrast, acknowledges that expectations for giving credit depend upon culture and community. By allowing students to engage with the logic of citation in different communities instead of asking them to follow regulations, instructors prepare them to discuss and debate the role of citation. Students can contribute to our understanding of what citation should be, if we give them the tools to understand what current expectations are and why they are what they are. What I am advocating here resembles the approach embodied by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say / I Say in that it focuses on teaching students how to join conversations in their writing. 4 Where it differs is in locating these conversations specifically within communities and in viewing these communities as authorities on the rules conversations should follow. Such a focus could be achieved without the online element, but using web writing for this task makes explicit the connections between activities many students engage in every day and the practice of citation in academic writing. Also, on the Internet, conversations happen faster and more visibly (thanks in large part to the use of hyperlinks instead of or in addition to more static forms of citation), making the communities in which they take place easier to observe and participate in, especially given the time limitations imposed by the length of a course.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Citation standards are developed by communities and codified by authorities, not necessarily in that order. A number of examples of how these two aspects of the development of expectations for giving others credit online can be given to students. Ryan Cordell has described using examples from social media to explain citation practices to students: “You wouldn’t steal somebody’s post on Twitter, he explains to them. Instead you mark it with “RT,” for retweet. Same with Facebook: ‘If you get something cool from someone, you tag them.’” Academic citation, similarly, shows where ideas comes from. 5 Descriptions of the connections between the logic of academic and of social-media citation can be much more detailed, however.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 5 The history of citation on Twitter provides examples that illustrate the importance of citation and of different kinds of citation practices. Users quote each other by retweeting. This feature only became automatic a few years ago. Originally, retweeting had to be done manually, by copying text and prefacing it with “RT @[username]”—a convention that became widespread on Twitter within a year of its launch. Some people on Twitter still use this method, especially when they want to add a comment before the quotation. (Sometimes the comment is placed afterwards, with a character such as “|” dividing the quoted material from the original.) “RT” is changed to “MT” (“modified tweet”) when the wording is altered. Less commonly used, and originating with blogs, are “via” and “h/t” (“hat tip”) to denote the intermediary sources of a link, MT, or RT. The early development of RT by Twitter users illustrates the importance online communities place on credit. The distinctions between “RT,” “MT,” and “via” or “h/t” show the value placed on accuracy in giving credit; they can be compared to academic citation practices for quotations, paraphrased passages, and intermediary sources. The inclusion of “@[username]” also has the function of creating a conversation, since the cited user receives a notification of the tweet from Twitter. Scholarly citation, too, is a kind of conversation, though certainly a less efficient one. On Twitter, linking to external articles is also a citational practice, especially when those links are prefaced with a quotation from or summary of the piece. This particular practice, however, is about more than credit: the whole article provides an additional, fuller context as well. One of the purposes of citation in online and academic communities is to allow one’s readers to access one’s sources. Finally, Twitter provides an example of how academic citation standards are formed by communities, as the Modern Language Association released a standard style for citing tweets due to demands from the community that uses the MLA style. A discussion of this particular example also provides an opportunity to illustrate that academic disciplines form communities.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 3 At the same time, not every borrowing of material on Twitter is expected to be cited. Memes in which specific phrases or pictures are played with and used to respond to different situations are rarely credited to their creators. To use an older, in Internet terms, example, no one ever provides a citation when they do something “for great justice.” Memes are an example of the kind of intertextuality that Susan Blum refers to when she describes students quoting media to each other without the kind of boundaries between the speaker’s and others’ ideas that academic writing requires. 6 In fact, web communities regard memes as a kind of common knowledge. Some pieces of common knowledge are, as Amy England argues, used to proclaim membership in a discourse community. 7 Only a newbie, someone who is new to a community and thus not fully cognizant of the community’s standards, expectations, and assumptions, would think that I invented Serious Cat if I tweeted a picture of him with the caption “Serious Cat. He’s seriously common knowledge.” That what is or is not common knowledge depends upon the discourse community presents a challenge for teaching, as students without direct experience within said community will struggle to judge precisely what knowledge is considered common. Newbies (to online communities or to academic disciplines) should proceed with caution, citing whenever in doubt and checking with more experienced community members along the way, but at least if they understand the dynamic nature of common knowledge, they will have a clear notion of knowledge in general as a constantly changing entity. 8

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

The widely-circulated Serious Cat meme.

The widely-circulated Serious Cat meme.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 In addition to describing the history of citation associated within a particular digital community, instructors can also assign students to observe and describe the citation practices of specific communities. The description can take the form of an essay, a blog post, or an oral presentation and can be completed individually or in small groups. In any case, making this project public (through an unprotected blog post or a recorded presentation uploaded to YouTube, for example) will potentially allow members of the community discussed to comment on whether they believe the students have accurately described their expectations. Students might also be encouraged to contact community members directly and quote or paraphrase them in their reports. Having students explore and consider the role of citation on the web in this way allows them to understand more deeply the uses of citation (perhaps even discovering functions unknown to the instructor) and to develop their abilities to adapt to the expectations for citation of different communities and disciplines.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 1 Online communities also provide examples of what happens when expectations for giving credit are not met, and when members of a community hold different expectations. Comments made during the controversies that ensue often demonstrate most clearly what different people consider the purpose of citation to be. Traci Gardner has described a lesson-plan on plagiarism, the Internet, and the public domain based around the Cooks Source controversy, in which a small magazine copied content from food bloggers without permission or sufficient credit; the initial discovery of a theft of material led to a crowdsourced effort to find all examples of plagiarized content and, further, to an online meme. Gardner suggests a number of pages on the incident that students can read before answering such questions as “Where are public domain materials on the Internet?” and “When do you need permission [to reproduce others’ work]?” 9

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 2 In the Cooks Source case, most online commenters agreed that the publication’s editor was in the wrong. A more controversial case occurred when white feminist blogger Amanda Marcotte of Pandagon was accused of plagiarizing the work of a woman of color blogger who, at the time, went by the pseudonym Brownfemipower. 10. The ensuing discussions, which took place in posts and comments on numerous blogs, considered not only the precise definition of plagiarism but also how issues of power and privilege affect citation. For many in the communities drawn into this debate, citing commentators representing less-heard perspectives is a matter of social justice. A blogger for major feminist blog Feministe, going under the name Holly (no surname), related the controversy to a broader context in which ideas espoused by people of color are not heard, let alone valued, until a white person restates them. 11 Failing to cite someone else’s work on a subject, whether through intentional plagiarism or a failure to fully explore what had already been written, is equally disenfranchising. Good citation requires good research first, and while the precise definition of plagiarism does matter, it is more important that students understand how to cite well. Instead of teaching the avoidance of plagiarism, we must teach the practice of good research and citation so that when composition students participate in conversations they do so as conscientious members of the communities in which they are writing.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Once students have practiced observing and analyzing the citation practices of online communities, the next step is for them to producing work embedded in such communities. Doing so provides students with experience of meeting standards and (potentially) being corrected by peers and authorities beyond the classroom. Moreover, as they become more involved in these communities, they also become more likely to continue participating and writing in them even after the course concludes. Online communities, even ones without specifically pedagogical aims, can support life-long learning.

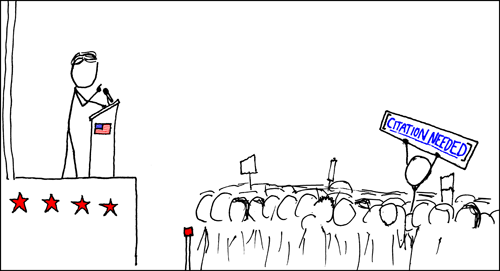

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 3 Given that the importance of citation to Wikipedia is so great that its designation for insufficiently sourced information (“[citation needed]”) became the subject of a web comic that spurred a meme, Wikipedia may seem to be an ideal community for this kind of project. Indeed, plagiarism and insufficient citation are generally caught quickly by Wikipedians—unless the edited page is unusually obscure. Recently, however, there has been some negativity among active, experienced Wikipedia editors towards such assignments because, they believe, student editors are more prone to making flawed edits that have to be reverted. 12 These stories can be used to frame assignments that involve editing Wikipedia pages, in order to emphasize the importance of understanding and following the community standards. How much of those standards will be presented in class and how much the students will be required to find and study independently should depend upon the level of skill they have demonstrated in their previous efforts at uncovering community citation standards.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Wikipedian Protester, holding ‘Citation Needed’ sign, comic by Randall Monroe, http://xkcd.com/285/.

Wikipedian Protester, holding ‘Citation Needed’ sign, comic by Randall Monroe, http://xkcd.com/285/.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 2 Another possible assignment to allow students to produce web-writing embedded in communities is for students to begin blogs designed to be part of a specific blogosphere (feminist, fandom, progressive, etc.). The disadvantage of this assignment is that, at least at first, the writing will be less immersed in the community; fewer readers from the community means fewer chances for the community to react if its expectations for giving credit are violated. The advantage is that, in order to make their blogs part of a community, students must cite blogs already established in the community, especially through links within blogposts that send trackback comments. Also, as part of the development of a blog, particularly if they are working in a small group, students should produce a stylesheet that includes details of a citation style that takes into account the expectations of the broader community to which the blog belongs.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 1 Indeed, a class creating web writing is itself a community. As such, it is entitled to develop its own standards for citation, though the development of these standards has to be constrained somewhat by membership in broader institutional and academic communities. It would be a disservice to allow students to decide, for instance, that they should be allowed to copy and paste whatever they want without any credit (and if students did suggest such a standard, it would likely indicate that they had not taken the assignment to develop standards seriously).

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 1 The required use of an existing citation style causes a great deal of anxiety among developing writers and, especially given the proliferation of formats in different disciplines, has questionable value in a general composition course. 13 When students are responsible for their own citation rules, instead of running a white-knuckle Google search for “MLA citation animated GIF linked Facebook hosted Tumblr” (for example), they can ask their classmates to decide on a standard, if time permits. Otherwise, they are more likely to be able to make a logical decision about how to cite a resource for which there is no specific citation format because they will have a thorough understanding of the reasons why their footnotes, endnotes, or in-text citations look the way they do.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 5 As part of the process of developing a standardized citation style, students might also be asked to consider whether it would suit any of the purposes of citation to name things that have contributed to their papers that are not usually credited in academic work. How much of the research process should be documented? At the end of a brief article on the effects of Google, Chris DiBona suggests an alternative approach to citation in the age of Google by listing the searches he undertook while completing the piece. 14 Certainly, a list of search terms would help readers discover the broader intellectual context of issues and ideas being discussed. Another example is software used by students. Should the word processor and citation manager appear in the bibliography? Scrivener and Keith Blount (its original designer) deserve credit for much of my current writing process.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 1 If students are using citation managers, they will need to learn how to customize the application’s output. Students using Zotero or Mendeley, for example, will have to create a Citation Style Language (.csl) file containing the specifications. There are also a few WordPress extensions that utilize this language to generate citations. 15 Though this step makes using the citation manager more complicated, it also presents an opportunity to improve digital literacy and to practice a skill that will be useful in the future should students find themselves required to prepare work in an unusual format.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Knowing what kinds of considerations go into the development of citation styles will allow them to understand whatever systems they may be required to use in the future and to make similar judgements later in life. Because they will be required to think about the placement of commas, full stops, and other punctuation marks, they will also have a greater awareness of the level of detail at which citation templates need to be read. Those students who go on to work in academia or in publishing may also be able to apply this experience to the revision of existing stylesheets and citation formats.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 3 Citation is not condemned to cramped footnotes in arcane tomes and term papers never read outside the classroom. Presenting citation rules without any indication of where they come from or how they connect to practices many students already engage in on a daily basis, however, allows students to think that it is. Perhaps even more troubling, many pedagogical approaches to citation focus not on engaging in good practices but on avoiding bad ones. This negative focus creates distrust of the online world, and, in the classroom, it builds a climate of fear. Instead of wanting to give credit where it is due and to participate in community conversations, conscientious students panic over periods versus commas in bibliographic entries and bend the language in awkward directions to ensure that they avoid patch-writing when paraphrasing. Less conscientious students try to game the system—doing just enough work to avoid (provable) plagiarism. Teaching citation through web writing will not prevent all such cases, but it has the potential to help students develop an internal motivation to practice good citation as defined by whatever communities they may participate in. Given an understanding of the reasons for existing citation practices, students can also contribute to discussions of when citation should happen and how it should look. They can shape the future expectations of communities both within and outside of academia. Preparing students to participate fully and rationally in whatever communities they might join after graduation is, after all, one of the most important goals of education.

¶ 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

About the author: Elizabeth Switaj is a Liberal Arts Instructor at the College of the Marshall Islands. She blogs at www.elizabethkateswitaj.net.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Notes:

- ¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

- Dan Greenberg, “We’ve Got a Monster on the Loose: It’s Called the Internet,” Brainstorm: The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 27, 2008, http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/weve-got-a-monster-on-the-loose-its-called-the-internet/5738; Jonathan Zittrain, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It (New Haven: Yale UP, 2008), 244, 317; Susan D. Blum, My Word! Plagiarism and College Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2009), http://books.google.com/books?id=J3uv5MQsdIkC&printsec=frontcover, 1; Thomas S. Dee and Brian A. Jacob, Rational Ignorance in Education: A Field Experiment in Student Plagiarism, NBER Working Paper Series (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2010), JEL No. I2,K4, http://www.swarthmore.edu/Documents/academics/economics/Dee/w15672.pdf, 3-4. ↩

- Lucy McKeever, “Online Plagiarism Detection Services—Saviour or Scourge?,” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 31, no. 2 (2006): 155–66; Marc Parry, “Escalation in Digital Sleuthing Raises Quandary in Classrooms,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, November 6, 2011, http://chronicle.com/article/Escalation-in-Digital/129652/; Charlie Lowe, “Issues Raised by Use of Turnitin Plagiarism Detection Software,” Cyberdash, September 7, 2006, http://cyberdash.com/plagiarism-detection-software-issues-gvsu. ↩

- Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition (New York: Continuum, 2000). ↩

- Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, They Say / I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010). ↩

- Parry, “Escalation in Digital Sleuthing Raises Quandary in Classrooms.” ↩

- Blum, My Word!, 7-8. ↩

- Amy England, “The Dynamic Nature of Common Knowledge,” in Originality, Imitation, and Plagiarism: Teaching Writing in the Digital Age, ed. Caroline Eisner and Martha Vicinus (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 104–113, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.5653382.0001.001, 100. ↩

- England, “The Dynamic Nature of Common Knowledge.” ↩

- Traci Gardner, “An Easy-as-Apple-Pie Plagiarism Lesson,” Bedford Bits: Ideas for Teaching Composition, November 23, 2010, http://blogs.bedfordstmartins.com/bits/plagiarism/an-easy-as-apple-pie-plagiarism-lesson/. ↩

- Problem Chylde, “Don’t Hate; Reappropriate,” Blog, Problem Chylde, April 8, 2008, http://problemchylde.wordpress.com/2008/04/08/dont-hate-appropriate/. ↩

- Holly, “This Has Not Been a Good Week for Woman of Color Blogging,” Blog, Feministe, April 10, 2008, http://www.feministe.us/blog/archives/2008/04/10/this-has-not-been-a-good-week-for-woman-of-color-blogging/. ↩

- Michelle McQuigge, “Toronto Professor Learns Not All Editors Are Welcome on Wikipedia,” National Post, July 4, 2013, http://news.nationalpost.com/2013/04/07/toronto-professor-learns-not-all-editors-are-welcome-on-wikipedia-when-class-assignment-backfires/; Nick DeSantis, “U. of Toronto Class Assignment Backfires in Clash on Wikipedia,” The Ticker: The Chronicle of Higher Education, April 8, 2013, http://chronicle.com/blogs/ticker/u-of-toronto-professors-class-assignment-backfires-in-clash-on-wikipedia/58225; “Wikipedia: Education Noticeboard,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Education_noticeboard. ↩

- Kurt Schick, “Citation Obsession? Get Over It!,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 30, 2011, http://chronicle.com/article/Citation-Obsession-Get-Over/129575/; Isaac Sweeney, “Throwing the Citation Handbook Away,” On Hiring: The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 23, 2012, http://chronicle.com/blogs/onhiring/throwing-the-citation-handbook-away/32581; Nels P. Highberg, “Plagiarism: An Administrator’s Perspective,” ProfHacker: The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 17, 2011, http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/plagiarism-an-administrator’s-perspective/31775. ↩

- Chris DiBona, “Ephemera and Back Again: Open Source and Public Sector, Google,” in Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net’s Impact on Our Minds and Future, ed. John Brockman, (New York: Harper Perennial, 2011), 224–27. ↩

- “The Citation Style Language,” CitationStyles.org, http://citationstyles.org/. ↩

This essay raises some very interesting points. I think you need to reframe the introduction to highlight your core argument – that citation practices are to be seen as positive, community-based norms, not punitive arbitrary rules – as that element only became clearer as I got into the essay. You might also want to mention the frequent conflation between citation/plagiarism and intellectual property/copyright issues – too often, I see students and educators claim that plagiarism involves copyright violations, which gets even muddier in web writing.

The editors invite you to revise & resubmit your essay, “Web Writing and Citation,” for the final draft of this volume. Our readers found your work to be intellectually engaging and thought-provoking, and your creative use of Twitter citation practices made many of us think about the topic in new ways, as Liz Bruno and others confirmed.

Several commenters suggested ways to strengthen your argument and exposition in your next draft. First, as Jason Mittell recommended above, consider rewriting the introduction “to highlight your core argument — that citation practices are to be seen as positive, community-based norms, not punitive arbitrary rules.” See also Kate Singer’s comment on para 10, which suggests that there may be an idea or argument in this portion of the essay that deserves to be moved closer to the front.

Second, as Barbara Fister and Jason advised, you may wish to separate the often-confused issues of citation versus copying in the opening to avoid diluting your argument.

Third, since this draft identifies “possible assignments” (para 14), it would be ideal if you could point readers to any examples you may have encountered over the past few months that move in this direction, if available.

The current draft word count is 3461 (as measured by WordPress), and the final version should not exceed 3500, so think carefully about making cuts as well as additions. The deadline for submitting your final draft is Thursday May 15th, though sooner is always better. This is a firm deadline, and if you do not meet it, we cannot guarantee that your essay will advance to the final volume. In the next few days, we will post further instructions on how to resubmit and edit your text in our PressBooks/WordPress platform.