Collaborative Writing, Peer Review, and Publishing in the Cloud

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 4 If you’re a currently a college faculty member, it’s likely that you came into the profession, or adjusted more than a decade ago, to using conventional word processing tools. Today on many campuses the most common writing implement is Microsoft Word, which prevailed over competitors such as WordStar, WordPerfect, and MacWrite during the 1980s and 1990s. 1 Word can be a wonderful tool, which I still rely upon when drafting much of my single-author scholarship. But around 2010 I began to realize how most of my student writing assignments were framed by what Word could do, and therefore limited by its constraints. Asking students to collaboratively author an essay, or simultaneously peer review each others’ work, or publish directly to the web raised many challenges because our primary word processing tool was not designed to teach this way.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 4 But the recent wave of networked writing tools — such as wikis, Google Docs, and web publishing platforms — have nudged more of us to rethink not only what is possible, but to reconsider the most preferable ways of integrating meaningful writing into a liberal arts education. For years we’ve told ourselves that it’s the writing that matters, not the technology, which was a comfortable stance. But what’s changed is that newer web technologies challenge our traditional norms of what types of writing matter. Think about the philosophical puzzle about the sound in the forest, and ask yourself: If a student writes a paper, and the professor was the only person who read it, was it real writing? Stated another way, if the deeper purpose of expository writing is to exchange ideas and convince readers to consider alternate points of view, then shouldn’t liberal arts faculty strive to create more authentically communicative writing assignments that engage authors and audiences, beyond the eyes of the individual professor?

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 3 If that mission sounds overwhelming, you’re not alone. Many college faculty consider ourselves unofficial teachers of writing, as we embrace its importance in our pedagogy, but never had specialized training in helping students to enhance their prose. We believe that we know good student writing when we see it, but have no formal background in the fields of rhetoric and composition. Moreover, it’s extremely difficult to keep pace with the dizzying array of newer digital tools — and the need to sort out which ones help or hinder our teaching — without feeling a bit older and more obsolete every day (while falling further behind on our grading). Therefore, it’s no surprise that many faculty simply rely upon the traditional word processors we’ve used for decades. In light of these real-world constraints, this essay offers some simple strategies and illustrations for integrating web-based writing, and argues that harnessing the inherent power of communities — both inside and outside of our classrooms — can make the writing process more authentic and meaningful for liberal arts education.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Collaborative Writing in the Cloud

Long before the web, innovative faculty began teaching collaborative writing techniques as a challenge to the tradition of solitary authoring. 2. The transition from typewriters to word processors made this technique easier to teach, as students could independently author text and assign one team member to merge it into one document, or collaborate on writing one document by passing it back and forth. Several faculty took co-authoring one step further with wiki tools, which allow multiple users to edit the same web-based document (as Mike O’Donnell and others have shown in this volume).

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 But the writing tool that dropped my jaw — and reawakened the pedagogical side of my brain — was Google Documents, which enabled multiple users to edit the same web document and view collaborators as they typed changes in real time, in contrast to the delayed view of editing in wikis. Looking back, I originally understood that users could upload and share files on Google Docs in May 2009, but didn’t fully grasp its multi-authoring features until 2010 at my first THATCamp (The Humanities and Technology Camp), where session organizers shared links to Google Documents for multiple participants to simultaneously share notes. If you’ve never seen collaborative writing in action, here’s a brief screencast of my students typing notes on the same Google Doc.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 2

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Screencast of simple crowd-writing exercise on Google Docs 3

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 1 Google Docs (and wikis) offer a “revision history” feature that allows readers to trace specific lines of text back to the original author, which permits individual assessment in collaborative writing assignments.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

In Google Docs, select File > Revision History to view changes by author in colored text.

In Google Docs, select File > Revision History to view changes by author in colored text.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Owners of a Google Doc may change the sharing settings (which are private by default) to allow viewing, commenting, or editing by the public, or anyone who has received the link, or invited guests by username.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

Google Doc share button.

Google Doc share button.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Google Doc sharing settings.

Google Doc sharing settings.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Google Doc visibility options.

Google Doc visibility options.

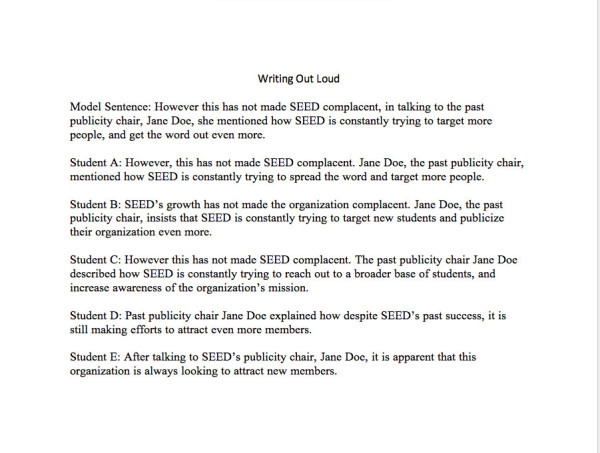

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 1 Four years after Google Docs was publicly released, college educators continue to invent new ways of incorporating this writing tool into their liberal arts classrooms, building on a shared sense of community to enhance learning. Some focus on simultaneous writing by individual students on the same page, while others emphasize collaborative writing of one document by multiple authors. Brandon Walsh’s “Writing Out Loud” activity illustrates the former, by modeling how individual authors try out alternate versions of a sentence — usually within the privacy of our minds — to make the editing process more visible and tangible for the entire class. “We usually turn to the exercise when a student feels a particular sentence is not working but cannot articulate why,” he explains. By pasting the original sentence into a Google Doc template and sharing editing privileges with the class, individual students can quickly suggest rewrites on their laptops, then discuss the merits of different approaches. From Walsh’s perspective as the instructor, this shared micro-editing process “allows you to abstract writing principles from the actual process of revision rather than the other way around.” 4

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 1

Brandon Walsh’s image from his “Writing Out Loud” template.

Brandon Walsh’s image from his “Writing Out Loud” template.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 A different teaching approach uses Google Docs as a tool for collaborative authoring of one group document. One technique is to assign two or more students to co-author a paper, as George Williams describes. 5 But another technique that builds up collaborative writing skills is to create a Google Doc for shared note-taking in class (as illustrated in the video clip from my first-year seminar above). 6

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 2 Both pedagogical approaches share a common vision of drawing upon the wisdom of the crowd, the belief that knowledge created collectively is richer than what individuals produce in isolation. Google Docs (and other collaborative authoring tools) can help transform the writing process from a solitary exercise into a community-oriented learning experience, which fits better with the broader purpose of teaching writing in a liberal arts context. That’s the spirit behind this entire volume. When my Trinity faculty colleagues and I began developing the concept for Web Writing, we did a simple “crowd-writing” exercise in fall 2012 to clarify what prospective readers expected from this book. First, I introduced the idea at a faculty workshop and asked participants to respond individually, through a free-writing exercise on a traditional paper handout, to this prompt: As a prospective reader, what would you like to see in this book? What topics or questions should be addressed? What kind of digital resources would be valuable to you?

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

Introduction to a crowd-writing exercise for Web Writing concept, September 2012.

Introduction to a crowd-writing exercise for Web Writing concept, September 2012.

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

Excerpt from crowd-writing exercise for Web Writing concept, Fall 2012.

Excerpt from crowd-writing exercise for Web Writing concept, Fall 2012.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 After individuals wrote down their responses, they moved into small groups to share and compare their hand-written notes. Next, each group was provided with a laptop or tablet to type their selected comments into a publicly shared Google Document, which appears as a screenshot below (and anyone can follow this link to read the original). 7

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 3 For many faculty in the room, this was their first experience with a real-time collaborative writing software such a Google Docs. The exercise forced them to consider new questions: Should they claim ownership of their words on the group document by adding their names? Should they hold back from placing untested ideas on a public document, where others could read them? By playing the role of learners, professors also gained new perspectives on whether or not these collaborative writing tools might fit within — or expand upon — their current teaching practices.

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

Peer Review in the Cloud

Like collaborative writing, many faculty integrated peer reviewing into their writing instruction years ago. Prior to digital technology, we asked students to exchange papers with one another. When shared networks became more common in the early 1990s, faculty at my campus and elsewhere created electronic folders, and set privileges to allow students to view and comment on other students’ drafts, to build a stronger community of writers. 8 Beginning in the late 1990s, many of us began using Learning Management Systems (at my campus, Blackboard, and then open-source Moodle) to allow the exchange of writing and commentary within our courses.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 But as my goals for broadening the peer review process expanded in 2012, I adopted Google Docs as a preferred platform because it supported real-time simultaneous commenting with multiple readers, inside and outside of our classroom. For my mid-level undergraduate Cities Suburbs and Schools seminar, our writing assignment was to create public history entries on housing, education, and civil rights topics for an open-access statewide history website, ConnecticutHistory.org. Clarissa Ceglio, one of the site’s editors, and I collaborated to craft a real-world writing assignment that would sharpen my students’ skills in communicating about controversial episodes from the past with broad present-day audiences, on specific topics in which they were quickly developing some expertise. 9 Our community learning partnership brought mutual benefits for all parties. Ceglio, an experienced writing instructor and editor, visited my seminar to explain the publication’s writing guidelines, and subsequently served as a peer reviewer and co-evaluator, which are duties that I gladly shared. My students wrote essays about our northern state’s hidden history on racial discrimination and reform struggles, which the publication was eager to receive. Each student selected a recommended topic and was required to submit two drafts for the class assignment, with the option to revise and resubmit a third draft to the publication, which did not guarantee to publish unless it met their high standards, often through subsequent revisions.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 2 Given our focus on single-author drafts with rapid developmental editing feedback from multiple student peers and our community partner, we quickly agreed on Google Documents as our platform. This was not a collaborative writing project, as each student was responsible for his/her own essay, but each writer needed to receive comments during a short timeframe from several readers, who would benefit from seeing each others’ feedback on broad concepts and granular details. Furthermore, Google Docs can handle academic requirements (such as footnotes), and students can easily import and export their writing back and forth to other word processors (such as Microsoft Word), allowing them to use the writing and revising tools that they prefer. In other words, I do not require students to compose their drafts in Google Docs, but work for the peer review stage must be submitted on this platform.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 1 To orchestrate this multi-party process, I created an Organizer page in Google Docs to guide students on how to link to their individual drafts for peer review and commenting (which other instructors may freely copy and modify for their own purposes). 10 First, I share the link to the Organizer page by posting it on the online syllabus (or instructors may post on a password-protected LMS to limit access to enrolled students, if desired) and temporarily open it up by modifying the Google Doc settings (Share > Anyone with this link can edit). Second, I demonstrate how students need to modify the sharing settings in their individual Google Doc drafts (or their blank starter pages) to allow peer reviews (Share > Anyone with this link can comment). Third, I show students how to copy the long link to their individual Google Doc drafts, then to my Organizer page, where they type their names (or initials), embed a link, and paste the long address to their individual Google Docs. After all students have done this step, I lock down the Organizer page by changing the settings (Share > Anyone with this link can view) so that no one accidentally edits the page. The screencast below illustrates these steps.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 2

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Screencast: How to Organize Peer Review on Google Docs 11

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 3 Organizing peer review with Google Docs allows multiple student readers (on campus) and our community partner (off campus) to simultaneously comment on drafts during a relatively tight turnaround period. When my students and I first tried this system in Fall 2012, the mechanics worked well but I failed to provide sufficient guidance on how to thoughtfully peer review a classmate’s writing. Students did not fully understand the difference between broad and narrow comments, nor the ideal placement of each type on the page, and several writers reported feeling overwhelmed when trying to sort through the feedback. To address this concern the following year, I asked students to paste the assignment criteria at the top of their Google Doc drafts before the peer reviews, and encouraged reviewers to place their broader comments there. Laying out the evaluation guidelines before the assignment, and visibly reminding students to refer to them during the peer review provides a common vocabulary for judging what makes “good writing” in this particular context. 12 For this ConnecticutHistory.org assignment, the current criteria are:

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 1) Does the essay open with a compelling argument or story that explains the significance of the topic to Connecticut history? Does it inspire readers to think in new ways?

2) Are the claims supported with appropriate evidence and reasoning? Is the historical research accurate and balanced, with full source citations?

3) Does the writing style engage broad audiences, and provide sufficient background for those unfamiliar with the topic? Is the text well-organized and grammatically correct?

4) For draft 2 only: Are digital elements (such links, images, videos) thoughtfully integrated into the web essay, and properly credited?

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 While not all student reviewers followed my advice on posting broader comments at the top (or found this to be a more difficult cognitive challenge), the placement of the evaluation criteria on the page helped me and the community partner to communicate more clearly, and we agreed that the second year’s comments were more focused than the first year. For comparison, see comments on this sample 2012 essay:

¶ 31

Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

Sample Google Doc peer review (2012), before adding evaluation criteria. Click to view original in new tab/window.

Sample Google Doc peer review (2012), before adding evaluation criteria. Click to view original in new tab/window.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Contrast with comments placed on the evaluation criteria at the top of a sample 2013 essay: 13

¶ 33

Leave a comment on paragraph 33 2

Sample Google Doc peer review (2013), after adding evaluation criteria. Click to view original in new tab/window.

Sample Google Doc peer review (2013), after adding evaluation criteria. Click to view original in new tab/window.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 4 Overall, the Google Docs peer review platform works far better than alternatives I’ve used in the past, such as emailing Word documents back-and-forth (aka “attachment hell”), or uploading Word docs to our college’s LMS (which lacks simultaneous real-time commenting, and does not allow instructors to easily add off-campus guests) or a Dropbox.Com folder (good for sharing files with off-campus guests, but they cannot simultaneously open and save comments on the same file). Moreover, while traditional blogs feature end-of-the-post comment boxes that imply summative evaluations, conducting peer reviews in this way with Google Docs encourages formative feedback to help students develop their drafts-in-progress, with both broad-level comments (in response to the evaluation questions at the top of the page) and granular line-editing (on any portion of the text). If your campus supports Google Apps, perhaps the setup process would be easier, but at my institution (which does not subscribe to this service), we still make it work through individual student accounts. To address concerns raised in my Public Writing and Student Privacy chapter (in this volume), I require peer reviewers to log in to receive credit (which places their name and timestamp on each comment), but allow students to create a separate Google Docs account under a different name if additional privacy is desired. Like all peer review assignments, the Google Doc platform requires an initial time investment by the instructor and an allocation of five to ten minutes of class for students to link up to the organizer page and learn the basics of inserting comments, but those cost are far outweighed by the additional out-of-class benefits of commenting to develop each other’s writing and building a stronger community of authors and readers.

¶ 35

Leave a comment on paragraph 35 2

Publishing in the cloud

After the hard work of drafting, peer reviewing, developmental editing, and revising, it’s a relatively simple step to teach my students to publish their work to the public web as a means to connect with broader communities of readers. My college supports a self-hosted multisite installation of the open-source WordPress blogging platform, which for selected courses I essentially use as a public Learning Management System (for my syllabus, open-access learning resources, links to student writing), while other aspects remain private on the password-protected LMS (such as student contact info and grades on our campus Moodle platform). While I’m fortunate to have campus WordPress support, several faculty at colleges and universities without this service have impressed me by creating their own free WordPress.com course sites that operate in very similar ways. Either way, most students learn the basics of how to post their first essay on a WordPress platform very quickly. Now in my third year of teaching writing with WordPress, I timed how long I spent teaching the basics to the 17 students enrolled in my first-year seminar, and it took 7 minutes (because they’re a smart class and asked several questions). The video tutorial screencast I share as a supplemental resource for students to replay at their own pace, covering the dashboard and user profile, pasting text into the visual editor, and adding basic links and images, takes only 4 minutes. For most students, WordPress is essentially just another word process, but one that publishes their work directly to the open web.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Video: How to Post on Trinity Commons WordPress v3.5, Fall 2013 14

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 2 As an instructor, I invested additional time learning how to operate WordPress to create a customized teaching platform for my courses. And I also spent time learning the inner-workings of my campus Learning Management System (Moodle), which I began teaching with around the same time as WordPress. But the payoffs for each platform are very different. With WordPress, the intellectual energy I spend on my teaching — designing syllabi, crafting learning resources, and helping students to develop their writing — becomes publicly accessible, attached with my name (and reputation). Based on anecdotal comments from professional colleagues and my personal web statistics, I know that many people look and find value in my open-access teaching materials, probably more so than my scholarship. But with a password-protected LMS, all of that effort is locked up inside a box, making it difficult (though not impossible) to share with others. Without a doubt, an open-access teaching platform reaches people far outside my classroom, thereby connecting me and my students with communities of people we may never meet face-to-face.

¶ 39

Leave a comment on paragraph 39 1

Student voices on community learning and web writing

While I’m still sorting out what my students do (and do not) learn with web writing tools in comparison to analog teaching methods, some experiences are hard to overlook, even if they may be atypical. For example, of the 11 students from my Fall 2012 Cities Suburbs and Schools seminar who completed the ConnecticutHistory.org assignment, 5 continued to revise their essays into Spring 2013 and eventually saw their works published on the community partner’s website. We video recorded an interview with 4 of the students (and a teaching assistant) to listen to how their perceptions of the process. 15

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Make Life Collaborative video: student voices begin around 1:00 16

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 1 “I struggle with writing” is a common theme among many students, even those who persisted with the process and made it to the publication stage. Academic writing can intensify this feeling because it is typically done in isolation. But even though these students each wrote individual essays, they identify it as collaborative work because they supported one another through the stages of the writing process, such as the multi-person peer review. Furthermore, these essays were written with a community partner in mind, for a broader purpose than just the professor’s eyes. “I really felt more like a contributor, like a colleague, rather than just a student handing in an assignment,” reflects Amanda Gurren. “We felt like we were working with people, rather than for them.” Seeing each others’ work appear on the ConnecticutHistory.org website, and hearing how a student in another class cited it, proved that they had contributed to the education of someone other than themselves. While many of us have taught long enough to remember hearing students express similar emotions on pre-Internet assignments, it’s also clear that web writing — with a broader purpose — has rich potential to connect us and engage us with broader communities.

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 Notes:

- ¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

- “Word Processor,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, November 23, 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Word_processor&oldid=524567947. See also a forthcoming literary history of word processing by Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, “On Tradecraft and Track Changes (An Update),” August 15, 2012, http://mkirschenbaum.wordpress.com/2012/08/15/on-tradecraft-and-track-changes/. For a free and open-source word processor and accompanying suite of tools, which some mid-2013 reviews claim is better than Microsoft Office, see Libre Office version 4.1 from the Document Foundation, http://www.libreoffice.org/. ↩

- Donald C Stewart, “Collaborative Learning and Composition: Boon or Bane?,” Rhetoric Review 7, no. 1 (1988): 58–83; Rebecca Moore Howard, “Collaborative Pedagogy,” in A Guide to Composition Pedagogies, ed. Gary Tate, Amy Rupiper, and Kurt Schick (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), cited in Emily Viggiano, “Teaching Tip Sheet: Collaborative Writing” (Writing Across the Curriculum, George Mason University, circa 2004), http://wac.gmu.edu/supporting/tip_sheet_collaboration.pdf. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, Simple Crowd-Writing Exercise with Google Docs, First-Year Seminar at Trinity College, Fall 2013, http://youtu.be/gH_Oe4QMyG8. ↩

- Brandon Walsh, “Writing Out Loud: Google Docs for Live Writing, Revision, and Discussion,” September 25, 2013, http://bmw9t.github.io/blog/2013/09/25/writing-out-loud/. ↩

- George Williams, “GoogleDocs and Collaboration in the Classroom,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, ProfHacker, June 14, 2011, http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/googledocs-and-collaboration-in-the-classroom/34075. On collaborative writing in general, see Jesse Stommel, “Theorizing Google Docs: 10 Tips for Navigating Online Collaboration,” Hybrid Pedagogy, May 14, 2012, http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/Journal/files/10_Tips_for_Google_Docs.html. ↩

- For shared note-taking with wikis, see Jason B. Jones, “Class Notes Assignment,” Professor Jones’s Wiki, 2009, http://jbj.pbworks.com/w/page/13150225/Class-Notes-Assignment. For shared note-taking with other tools, see Kris Shaffer, “Collaborative Note-taking in Class,” September 16, 2013, http://kris.shaffermusic.com/2013/09/collaborative-note-taking-in-class/. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, “Web Writing: A Guide for Teaching and Learning,” Trinity Center for Teaching and Learning fellows workshop, September 2012, http://bit.ly/WebWritingIdeas. ↩

- At Trinity College, my Writing Center colleagues began experimenting with shared network folders for portfolios and peer review in 1991, as described by Beverly C. Wall and Robert F. Peltier, “‘Going Public’ with Electronic Portfolios: Audience, Community, and the Terms of Student Ownership,” Computers and Composition 13, no. 2 (1996): 207–217, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(96)90010-9. At the same time, my high school faculty colleagues and I also created shared network folders for peer reviewing in our tenth grade curriculum: Keith Corpus, Jack Dougherty, and Jeff Reardon, “Newark Studies: Relevancy Is Key to Interdisciplinary Curriculum for Improving Writing Skills,” THE Journal: Technological Horizons in Education 19, no. 4 (October 1991): 44–47, http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=121244.121259. ↩

- Jack Dougherty and Clarissa Ceglio, “Assignment: Compose Web Essay for ConnecticutHistory.org,” Cities, Suburbs, and Schools seminar, Trinity College, Fall 2012 and recently revised, http://commons.trincoll.edu/cssp/seminar/assignments/connecticut-history-entry/; CTHumanities, ConnecticutHistory.org, http://connecticuthistory.org. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, “Instructor’s Organizer page for sample peer review,” Google Doc created for Web Writing book, Fall 2013, http://bit.ly/OrganizerPeerReview. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, How to Organize Peer Review on Google Docs, YouTube video, 2013, http://youtu.be/pwMQ2zDLrfk. ↩

- For a richer discussion of this topic, see Heidi A. McKee and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, eds., Digital Writing Assessment and Evaluation (Logan, UT: Computer and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013), http://ccdigitalpress.org/dwae/. ↩

- Amanda Gurren, draft of “Project Concern: city-suburb integration program,” Fall 2012, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-sd_2t5JPCLOD9kkWaVo8x30A_Ah9hg7IHPY03HqBtc/edit and Emily Meehan, draft of “How Racist Actions of Housing Committees Shaped the Demographic of Hartford Today,” Fall 2013, https://docs.google.com/document/d/15IxYNRGDSe4UMGlvbrhzPocRRljaDsQ-C9TZy7lNo_A/edit, both from my Cities Suburbs & Schools seminar, Trinity College. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, How to Post on Trinity Commons WordPress V3.5, YouTube video 2013, http://youtu.be/fzfPG9k__hs. ↩

- See links to the students’ essays at “Trinity College Students Call Attention to Histories of Inequality,”ConnecticutHistory.org, May 2013, http://connecticuthistory.org/trinity-college-students-call-attention-to-histories-of-inequality/. ↩

- CTHprograms, Make Life Collaborative, YouTube video 2013, http://youtu.be/NuWg9Jrkrpw. ↩

This essay is more descriptive than analytical, but deeply helpful nonetheless. I’m inspired to write a blog post about planning my DH class for spring.

Understood, though sometimes I find that the process of figuring out which parts need to be described to broad audiences, and how best to accomplish this, turns out to be an analytical writing exercise.

This reminds me of the way Writing Out Loud works – by analyzing specifics, you can get to generalities rather than goingt the other way around.

I really enjoyed this essay. It has a lot of practical information and how-to, but it presents it while also making a strong case for collaboarative and public writing.

The only thing I wondered – are there things that worked better in the past? Things students struggle with? Things you left out of the syllabus to make room for this kind of collaborative assignment? Are there times you deliberately choose not to promote tech-enabled collaboration or public writing and, if so, what are the pedagogical reasons – or are they logistical?

I think the description/analysis balance is well-pitched, as the concepts are articulated in iterating the choices made, and then reflected upon via what students did & how it compared to other platforms. I think the essay works really well as applied pedagogical reflection!

I really enjoyed this essay for the reasons others have listed above as well as the videos and visuals that provided additional depth for the reader.

I think this is a great essay for those who haven’t used Google Docs as a writing tool in the classroom–particularly for revision. It gives a “how to” guide, with some suggestive comments near the end about why Google Docs is such a good technology for iterative, self-reflexive revision. As someone who has used Google Docs before, I was hoping to hear a bit more in-depth analysis (as Amanda suggests) maybe around paragraphs 29/30 about how the structure of commenting (and perhaps the whole scaffolding of the technology) makes comments and revisions better. Part of me wanted to understand in more depth what kinds of comments students gave and why. More specifically, how can Google Docs get students to move past (I liked this part/I was confused about this part) toward more substantive commenting.

Thanks for asking me to elaborate on specific sections of the essay. This semester I’ve been tracking students’ peer commenting more carefully, and digitally archiving their feedback in stages, which I plan to analyze and incorporate into the next draft.

The editorial team has accepted this essay (with revisions), and appreciates comments from readers, which will inform the final draft.