Introduction

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 6

Why this book?

Web Writing responds to contemporary debates over the appropriate role of the Internet in higher education. On one hand, proponents of massive online courses preach the benefits of large-scale lectures and machine-driven assessments. On the other, skeptics reject new technologies as shallow substitutes for true learning, yet cling to fading visions of the past. As the editors of this volume, we steer a middle course that argues for wisely integrating web tools into what the liberal arts does best: writing across the curriculum. Whether a persuasive essay, scientific report, or creative expression, all academic disciplines value clear and compelling prose. The act of writing visually demonstrates how we think in original and critical ways, and more deeply than what can be taught or assessed by a computer. Furthermore, learning to write well requires engaged readers who encourage and challenge us to revise our muddled first drafts and craft more distinctive and informed points of view. Indeed, a new generation of web-based tools for authoring, annotating, editing, and publishing can dramatically enrich the writing process, but doing so requires liberal arts educators to rethink why and how we teach this skill, and to question those who blindly call for embracing or rejecting technology. At this critical juncture, our book can deepen conversations on writing and the web across college campuses, and perhaps reframe debates about the value of higher learning in the digital age.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 4 Our book builds on existing scholarship on rhetoric, pedagogy, and technology, but intentionally broadens the discussion to reach wider audiences across the liberal arts. While our five-member editorial team includes specialists in composition, digital humanities, and developmental learning, the book’s sponsorship by the Trinity College Center for Teaching and Learning signals our commitment to fully engage with faculty members in the arts, humanities, social sciences, and physical & life sciences. We draw inspiration from ProfHacker, a widely-read group blog hosted by the Chronicle of Higher Education, which connects academics from all disciplines on teaching and technology issues. 1 We also have learned from innovative digital publications such as Kairos, and Writing Spaces, the Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, and Debates in the Digital Humanities. 2 Our book aims to broaden participation by liberal arts faculty who do not identify with the fields of composition studies or digital humanities, yet are fully engaged in the teaching of writing, and looking for guidance on how to make sense of rapidly changing technology. Interestingly, higher education lacks a comprehensive book on teaching digital writing that is comparable to titles authored for the K-12 sector by Troy Hicks and the National Writing Project. 3 Web Writing seeks to correct this imbalance by contributing to the scholarship of teaching college-level writing in the digital age.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 2 We did not design the book as a high-theory study of composition, nor did we envision it simply as a high-tech user’s guide. Instead, Web Writing seeks to bridge philosophical and practical questions that arise from the experiences of liberal arts educators at this challenging point in time. What are the most — and least — compelling reasons for why we should integrate web writing into our curriculum? Which digital tools and teaching methods deepen — rather than distract from — thoughtful learning? How does student engagement and sense of community evolve when we share our drafts and commentary on the public web? To what extent does writing on the web enable our students to cross over divisive boundaries, and what new barriers does it create? The book’s subtitle signals our desire to blend “why” questions with illustrations of “how” it can be done, presented on an open-access digital platform that integrates essays, commentary, online examples, and tutorials.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 2 We also aim to push forward on the realm of what is possible — and desirable — regarding web-based technologies and higher learning. Let’s pull away from the massive open online course (MOOC) debate for a moment and focus on what liberal arts colleges do best. We teach clearer thinking on divergent points of view through careful reading, listening, and most importantly, writing. If this book prompts faculty (and students, academic staff, administrators, and trustees) to reconsider why and how we teach and learn about writing, to engage in deeper conversations about pedagogical potentials and realities of the web, and perhaps to try a different approach in class next week (or next semester) and reflect on its outcomes, then our primary objectives will be met.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 1

Where’s the evidence on web writing and student learning?

Back in the old days (circa 1980s), with the birth of Writing Across the Curriculum, peer review was seen as a mechanism to ratchet up the stakes for students as they worked on writing assignments. In this approach, faculty members could be assured that at the very least, they were not the first and only person to ever have read a student’s paper. Moreover, there was the belief, or at least the hope that by providing students with a different audience — their peers — they would see their work differently and take the process of writing and rewriting more seriously. No longer would writing be seen as a purely independent process “owned” by the student to be “given” to the professor.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 1 But some liberal arts faculty members expressed skepticism at that time about whether peer review really improved student learning or was simply a waste of time. While students may have reported that the process helped them reformulate their ideas, and instructors’ personal intuitions convinced them that final drafts were stronger, the question still loomed — was there “real” evidence of improvement? The good news — both for doubters and true believers — is that there is now a significant body of research on the positive effects of the peer review process, including studies based on “real” experiments, such as those comparing groups of students who received peer feedback versus those who did not. These results provide solid evidence of student learning that move the discussion beyond interesting, yet basically impressionistic, accounts of individual teachers.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 6 Fast forward to the present, where the peer review process is reaching new levels. With the advent of technologies such as wikis and Google Docs, today’s students can not only comment on their peers’ work, but more easily review comments written by others and simultaneously collaborate on co-authored assignments. All of this changes the landscape of our work as teachers, yet once again we must ask ourselves whether it leads to improvements in student writing and thinking. Fortunately, researchers are now providing us with some answers, using the same scientific method of comparison and control groups. One study by Ina Blau and Avmer Caspi illustrates this trend. 4 They compared collaborative student work on Google Documents across different conditions to determine how the act of suggesting revisions (by inserting marginal comments) versus directly editing a peer’s text influenced their sense of ownership, responsibility and perceived quality of writing outcomes. While the researchers found that suggesting revisions through commenting yielded the greatest benefits, the key point to emphasize is how their work demonstrates more systematic ways to evaluate methods of web writing on student learning outcomes. Clearly, more research is needed to understand, for example, if all students (e.g., novice vs. seasoned writers) will benefit equally from the same teaching technologies or how certain types of online collaboration might help or hinder different aspects of writing (e.g., grammar, organization, argumentation). Knowing answers to these types of questions might help us to persuade even our more resistant faculty colleagues into reimagining how we might teach with newer web technologies and approaches to student learning. While only a few contributors to the current manuscript directly address this question of evidence, we believe that Web Writing can draw more attention to the issue and stimulate broader discussion of the outcomes we desire in a liberal arts education in the digital age. 5

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 5

Why create a free web-book, with open peer review?

Since we could not find a book about writing on the web that met our needs as liberal arts educators, we decided to create one, and to publicly invite contributors to shape its direction with us. As academic authors, our goal is to share each stage of Web Writing on the public web — from initial ideas, to drafts with commentary, to the final manuscript — to make the scholarly writing and reviewing process more transparent, and to welcome ideas that will enhance the volume before its final publication. If you’re familiar with the concept of “flipping the classroom,” then consider this analogy to “flipping the book.” First, authors publish their drafts on the open web; second, expert reviewers and general readers share feedback to inform editorial revisions and final selections. This “publish-then-filter” approach, as Clay Shirky and others have described it, is not without risks, particularly for authors whose work may receive negative comments, or not advance to the final volume. But the rewards are numerous, greater opportunities for developmental editing by experts and general readers, reduced social isolation of the solo academic writing process, and speedier time from concept to publication. 6 Our model certainly beats the “old” way of constructing an edited volume, where individual contributors submitted chapters to an editor, but rarely saw drafts by others authors until the book was finished, thereby missing an exchange of ideas that would have enhanced the volume as a whole. Especially for those of us writing about digital influences on higher education, where rapid transformations outpace old-fashioned publication schedules (typically two years or longer), we are willing to embrace change.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 4 But as educators, a more compelling reason for constructing our book online is because that’s essentially what we’re asking our students to do when we assign them to share their writing with us and other readers. One of our hopes for Web Writing is to facilitate more faculty members into roles as authors and commentators of ideas on the web, to model richer forms of learning and teaching that might transfer into their classrooms. If you’ve ever required your students to post their words on your institution’s learning management system (such as Moodle, Blackboard, etc.), or to share their thoughts on the open web, then be sure to try it yourself by uploading your own writing for feedback from peers and/or the public. For many of us, our first experiences in widely circulating draft works was equally terrifying and exhilarating. But writing definitely improves with an audience. Moreover, publishing an open-access book does not require direct payments by our cash-strapped students (or our colleagues and college libraries) to advance the distribution of knowledge. By making Web Writing freely accessible, rather than locking it behind a password or a pay-wall, we broaden readership and increase learning opportunities for all involved. In fact, college educators may wish to share links to selected essays from our web-book with their students — particularly those with vivid reflections, examples of student writing, or online tutorials — and also invite them to “talk back” to the authors during (or after) the open peer review.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 4 Recent innovations in open-source technology and progressive academic publishing made it easier for our editorial team to create Web Writing in this public digital format. Tools such as WordPress have become easier to use, gained more support by educational institutions, and tailored toward scholarly review and publishing with recently enhanced plugins, such as CommentPress and PressBooks. (Learn more by reading “How our website works” in this volume.) In addition, we are fortunate to collaborate on this book with Michigan Publishing, the primary academic publishing division of the University of Michigan, which leads a growing number of academic presses with open-access options. Based and funded through the university library, their mission is to “create innovative, sustainable structures for the broad dissemination and enduring preservation of the scholarly conversation,” which matches our goals in this online edited volume. 7 The full text of our draft volume is publicly available during the open peer review, which is compatible with our publisher’s intent to make the final product available in at least two formats: print-on-demand (for sale) and open-access online (for free). Furthermore, working with Michigan Publishing and the HathiTrust Digital Library ensures long-term electronic preservation of the completed volume. In exchange for this support, our book contract is not likely to yield any royalties (but academic authors in our fields rarely make money from edited volumes, so there’s essentially no change in the status quo).

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 3 While open-access means free to readers, it does entail costs to produce. Yet rather than relying on post-production book sales revenues from individuals and institutional libraries, our home institution, Trinity College, directly funded approximately $5,000 in pre-publication costs (and indirectly supported knowledge and technical infrastructure costs), which improves the quality of the book while simultaneously raising the reputation of the campus among digital innovators. First, the Center for Teaching and Learning provided a $2,000 fellowship for a faculty member to conceptualize and draft the initial stages of the project during a 2012-13 seminar series. Second, the Center provided five $300 subventions to outstanding essay proposals by non-tenure-track authors, plus $500 to the Michigan Publishing to cover half the cost of commissioning four expert reviewers at $250 each. Third, the Trinity Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies awarded the editorial team a manuscript fellowship to sponsor a half-day seminar discussion of the manuscript in October 2013, with four guest readers from the college and one more from a nearby institution. Additional costs could be attributed to faculty and staff labor, and the technological infrastructure, but all of these were already in place and would have been spent regardless of this particular book project.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 4 The hardest part of constructing a multi-authored book on the web is not the technology or the dollar costs, but the social and organization arrangements. When you break away from the normal routines, it’s requires thinking ahead about alternate routes and clearly communicating expectations with all parties. For example, our first book proposal flopped, largely because the editorial team’s initial goals were unclear and did not align with those of the prospective publisher’s series editors. Fortunately, the University of Michigan Library announced its Maize Books imprint, which we found to be very compatible with the scope and aims of this volume, though others disagree with this direction for scholarly publishing. 8

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 During Web Writing open call for essay ideas and proposals (April-June 2013; in this volume), we invited prospective authors and readers to post one-paragraph topics that they would like to contribute or see others write about for the book. We welcomed essays with first-person perspectives and student-authored content. Editors and others readers posted comments to encourage contributors to deepen and develop their ideas into full drafts of 1,000 to 4,000 words by the mid-August deadline, with additional time to edit and format their work on our WordPress/CommentPress platform, which also supports footnotes, external links, screenshots, and video clips. But we continually emphasized the quality of the writing, and made clear our expectations for insightful and imaginative prose, support with rich examples, presented in a clear and compelling style that entices readers to scroll down the page and learn more.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 We also spelled out our Editorial Process and Intellectual Property Policy (in this volume), and required contributors to review and sign their agreement before submitting their full draft. In simple terms, it states that all contributors (and commenters) retain the copyright to their work, but agree to freely share their content under our Creative Commons license BY-NC (by attribution, non-commercial). Moreover, there is no guarantee that submitted essays will be published in the book. The Web Writing editorial team will select essays to be included in the final manuscript, based on our judgment of its quality and relationship to the volume as a whole, as shaped by the open peer review commentary. In November 2013, we anticipate sending invitations to selected contributors to revise and resubmit their work, and we expect to send private emails to others whose work we determine will not advance to the final volume. While essays that spark thoughtful online commentary are more likely to succeed than those which do not engage reader feedback, the editorial team will base its judgment on the quality of the essays, not the number of hits received by each web page.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 We deliberately scheduled our open peer review from September 15th to October 30th, to line up with the first (and saner) half of our fall semester at Trinity College and many North American academic institutions. In contrast to traditional blind peer review (and several question whether it truly is blind), Web Writing requires all commenters — both expert reviewers and general readers — to use full names. Anonymous comments are not permitted, and it is the editors’ responsibility to remove any language deemed inappropriate. But to avoid deferential treatment (and to add a bit of intrigue), we decided not to publicly reveal the identities of the four expert reviewers commissioned by the publisher during the open peer review. While readers may guess, and the reviewers may choose to make their designated roles known during the process, past experience with open peer review strongly suggests that the quality of commentary is not necessarily related to one’s official status in the academic world. We’re still in the experimental stages; let’s see what happens this time.

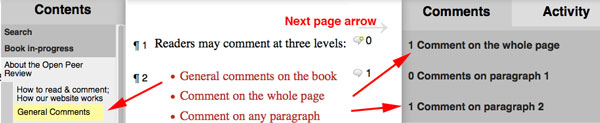

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 1 Careful readers will note that the current manuscript ends abruptly with a section titled “Conclusions to come.” Simply put, the end of this book has not been written, and we encourage you to join us in doing so. After the open peer review phase of Web Writing ends on October 30th, the editors will invite up to three of the most thoughtful commenters to revise and expand their selected responses and contribute them to be part of our broader conclusion for the final book, to be published in 2014. 9 We remind all readers to share your questions, criticisms, personal reflections, and reading suggestions by posting comments at three levels:

- ¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

- General comments on the book

- Comment on the whole page

- Comment on any paragraph

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

See also the Special Pages at the bottom of the Contents sidebar to view All Comments, or a list of Comments by Commenter.

¶ 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks go to several people who nourished Web Writing in its early stages: The inaugural group of Center for Teaching and Learning Fellows who kindly provided feedback on the first draft (Kath Archer, Brett Barwick, Carol Clark, Luis Figueroa, Irene Papoulis, Joe Palladino), and several colleagues who offered early advice and encouragement, specifically Korey Jackson, Kristen Nawrotzki, colleagues at MediaCommons, and many THATCamp workshop participants. Carlos Espinosa at TrinfoCafe.org capably manages the server that hosts our web-book. Christian Wach developed this version of the CommentPress Core plugin (based on a previous version by Eddie Tejeda) and patiently answered several questions about customizing our child theme. Our logo was designed by Rita Law, manager of creative services at Trinity College. At Michigan Publishing, we thank editorial director Aaron McCullough and his colleagues Meredith Kahn, Christopher Dreyer, Kevin Hawkins, and Tom Dwyer.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 The Web Writing editorial team:

- ¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

- Jack Dougherty, Associate Professor of Educational Studies

- Dina Anselmi, Associate Professor of Psychology and Co-Director of the Center for Teaching and Learning

- Christopher Hager, Associate Professor of English and Co-Director of the Center for Teaching and Learning

- Jason B. Jones, Director of Educational Technology

- Tennyson O’Donnell, Director of the Allan K. Smith Center for Writing and Rhetoric and Allan K. Smith Lecturer in English Composition

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 at Trinity College, Hartford, CT

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Notes:

- ¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

- Jason B. Jones, a member of our editorial team, is a co-founding editor of ProfHacker, http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/. ↩

- Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, http://www.technorhetoric.net/; Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing series, http://writingspaces.org/; The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, http://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/; Matthew K. Gold, ed., Debates in the Digital Humanities (Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2012), http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/. ↩

- Troy Hicks, The Digital Writing Workshop (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2009), http://digitalwritingworkshop.wikispaces.com/; Dànielle Nicole DeVoss et al., Because Digital Writing Matters : Improving Student Writing in Online and Multimedia Environments (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010), http://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/books/digitalwritingmatters; Troy Hicks, Crafting Digital Writing: Composing Texts Across Media and Genres (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2013), http://digitalwritingworkshop.wikispaces.com/Crafting_Digital_Writing. ↩

- Ina Blau and Avner Caspi, “Sharing and Collaborating with Google Docs: The Influence of Psychological Ownership, Responsibility, and Student’s Attitudes on Outcome Quality,” in Proceedings of the E-Learn 2009 World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, & Higher Education, Vancouver, Canada (Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 2009), 3329–3335, http://www.openu.ac.il/research_center/download/Sharing_collaborating_Google_Docs.pdf. ↩

- An earlier version of this section appeared in Dina Anselmi, “Peer Review on the Web: Show Me the Evidence,” MediaCommons, May 22, 2013, http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/question/what-does-use-digital-teaching-tools-look-classroom/response/peer-review-web-show-me-eviden. ↩

- For a richer exposition of the “publish-then-filter” argument, see Clay Shirky, Here Comes Everybody : the Power of Organizing Without Organizations (New York: Penguin Press, 2008); Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy (NYU Press, 2011), with open peer review draft (2009) at http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/mcpress/plannedobsolescence/; Kristen Nawrotzki and Jack Dougherty, “Introduction,” Writing History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming fall 2013), with open peer review draft (2011) at http://WritingHistory.trincoll.edu. ↩

- “About Michigan Publishing,” University of Michigan Library, 2013, http://www.publishing.umich.edu/about/. ↩

- For discussion (and some debate) about the Maize Books announcement, see Meredith Kahn, “Announcing Maize Books, A New Imprint for Scholarly and Creative Works,” University of Michigan Press Blog, May 1, 2013, http://blog.press.umich.edu/2013/05/announcing-maize-books/; Jack Dougherty, “Questions for Maize Books at University of Michigan Press,” May 3, 2013, http://commons.trincoll.edu/jackdougherty/2013/05/03/maize/; Meredith Kahn, “Maize Books Q&A with Jack Dougherty,” University of Michigan Press Blog, May 10, 2013, http://blog.press.umich.edu/2013/05/maize-books-qa-with-jack-dougherty/; and see also the comments in Barbara Fister, “Maize Books: Michigan Publishing Sows a New Imprint,” Inside Higher Ed, May 13, 2013, http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/library-babel-fish/maize-books-michigan-publishing-sows-new-imprint. ↩

- The reader-contribution conclusion idea is drawn from Jack Dougherty, Kristen Nawrotzki, Charlotte D. Rochez, and Timothy Burke, “Conclusions: What We Learned. . ,” Writing History in the Digital Age, forthcoming Fall 2013 and online at http://WritingHistory.trincoll.edu. ↩

One thing I like very much about this introduction is that it makes the decisions and processes involved in academic publishing transparent and questions why we have certain practices – such as the fairly common experience of contributing an essay to a collection but not knowing what the whole project looks like until it’s published. (The editors may do something to weave the contributions together in the intro, but the authors often have no idea that a point they made would be better argued if they knew the neighboring essay would bring up a related but different approach.)

So many of our traditions were accomodations made for a print-based medium. Even if we don’t change our practices, we can question them in new ways. Huzzah!

I agree that the meta-reflexivity and openness of this intro is welcomed. I do think you need to signpost this a bit more, explaining what an iteration of the book’s production and editorial process yields in terms of the issues it raises.

Yes, perhaps we should begin the conversation by asking this simple yet vitally important question of our higher-ed colleagues: Is your syllabus publicly available, or locked inside a password-protected site? Who made this decision, and why?

Not sure if this is the appropriate place to put this comment, but I see the general direction of this entire project aiming at a very open-access and very public form of web writing, which I think has its place. But I teach gender and women’s studies in an international setting and we talk about very sensitive subjects. For example, I dedicate at least one session and sometimes two to the topic of sexual violence. I always have my students participate in some sort of journal assignment (both online and offline) and you would be surprised how many journal entries I receive in which students disclose their own personal experience with sexual or other violence. I haven’t read all the contributions yet but I think at some point the volume needs to address how student writing will change depending upon whether it is on or offline. I doubt that my students would so easily connect the literature on rape in wartime to their own personal experiences if it were online. Perhaps there needs to be discussion about how writing changes when exported to the web, and how to balance the online and offline writing experience?

I think this is an important question to consider. Several projects exist to share syllabi, such as the Open Syllabus project, http://opensyllabusproject.org. Yet, it is still difficult to convince instructors to share their syllabus.

I like that idea! it makes the issue concrete by pointing out the implications of an everyday but often unreflective act.