Sister Classrooms: Blogging Across Disciplines and Campuses

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 6 Blogs are changing the way we communicate. Their hybrid form — a strange mix of private thought and public comment, diaristic timing with archival scope, and documentary solidity coupled with hypertextual fluidity — evokes the extraordinary shifts in cognitive processing that, some experts contend, are shaping the way today’s college students learn to read. 1 Hundreds of topics once bound to their own unique forms and fora have now been adapted to this new genre, as our politics, our hobbies and obsessions, our travels, and even our personal stories find their way into the ever-expanding blogosphere. But for all their range and flexibility—and, we might add, for all their immanent readability—are blogs really a suitable format for student writing? Can blogs truly stimulate and strengthen the critical and creative thinking we hope to develop in our students?

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 5 Any useful answer to this question will have to start with our expectations for student writing. Traditionally, college writing assignments ask students to demonstrate a mastery of both content and argumentation. (Perfect grammar would also be nice). Multiply this expectation across the range of fields and writing assignments that a student is likely to encounter in her journey through higher education and you set a rather lofty goal: a student who can fluently speak the distinct languages of half a dozen or more academic subjects, each with its own vocabulary and distinct disciplinary grammar. This kind of expertise seems an appropriate goal for a student’s major and minor subjects, but is discipline-specific writing, with all its particularities and palimpsests, really the best way to introduce non-majors to our fields?

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 12 The important question in this case is how we want students to use the writing assignments we give them, and it is here that blogs have an extraordinary potential. As a collaborative class effort, intimately linked to the intellectual work we do in the classroom, a course blog can create a uniquely powerful learning community that invites students to learn through writing, rather than using writing as a means to prove mastery. Writing to a digitally-mediated audience of their peers allows students to re-articulate new ideas, test applications, link to related resources, and affirm or modify the ideas their peers bring forward. In performing each of these functions, students can begin collectively to teach one another new concepts without having to take on the authoritative role of the expert.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 7 The momentum a class blog can create derives in part from the fact that it reinforces the social structures that are inherently a part of learning in a class. Although blog discussions are typically conducted asynchronously, created in the absence of faces, voices, and the other non-verbal cues that help us understand face-to-face conversations, this does not preclude them from being deeply social. In fact, as Randy Garrison has argued, participants in student blogs will often substitute interpersonal behaviors such as nodding or raising eyebrows with verbal equivalents such as “I agree with [Sandy]’s comment” or “I think [Mark] is making a different point.” Students will also use inclusive language, for instance “As we’ve already discussed,” to keep track of or redirect the discussion, suggesting a shared learning experience, a shared endeavor. Garrison suggests that, “Reaching beyond transmission of information and establishing a collaborative community of inquiry is essential if students are to make any sense of the often incomprehensible avalanche of information characterizing much of the educational process and society today.” 2 If this is so, then class blogs can help students to become more conscious of just what holds that community of inquiry together.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 5 But what makes this digital community different from a traditional discussion-based classroom? Time is one important factor. In a course blog, students have more time to reflect on the materials posted and the questions posed, and more time to shape thoughtful and responsive answers. And while the asynchronicity of blogging can be frustrating for those of us trained in the art of live discussion, it does allow students to engage in course material when and how they wish to, creating an opportunity for deep immersion with the subject at hand. Moreover, it grants them a far wider range of responses: in their contributions, they can (and frequently do) link to and discuss related resources and current events, post illustrations and photographs, and use personal reflections—i.e. “I believe we have an obligation to protect women’s rights, so I found this article very troubling”—as a pathway to scholarly discourse. The relative freedom of a blog post may also encourage students to take intellectual risks that feel less possible in the high-stakes, rigorously evaluated context of a formal paper. With increased time and latitude to write, students often produce surprisingly sophisticated responses to the questions we pose.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 2 Class blogs can also teach students that writing—and writing well—is rewarding. As a collaborative document, a blog offers immediate feedback on material posted, an affirmation that usefully parallels students’ experience with social networking sites. A particularly insightful or articulate observation will often be recognized and acknowledged by a student’s peers (or a watchful professor). A great post or comment can even resurface in class discussion, as teachers and students connect the learning taking place in digital space to the progress of the course itself. A post that becomes a useful part of the class’s learning is a nice accomplishment for a young writer. Even more importantly, it models the synthesizing process of academic discourse and peer review in a way that traditional assignments, with their more limited audience and impact, cannot easily do.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 7 So how can we actually build a successful student blog? To answer that question, we want to turn to our recent teaching collaboration, which matched Dr. Hagood’s environmental literature class at Hendrix College with Dr. Price’s environmental demography class at Furman University. These “sister classrooms” came together through interlinked blogs that gave students the opportunity to discuss environmental issues from their respective disciplinary angles and, as each class had a strong place-based focus, from differing regional contexts as well. 3 Our blog correspondence was complemented with teleconference meetings scheduled throughout the semester that brought the two classes face-to-face to discuss three classic texts of the American environmental movement. While the approach to these intercampus connections varied with each classroom, our students showed a consistent desire for the intellectual community of their sister classes, suggesting that web writing, with its rich potential for collaborative learning, has an important role to play in improving learning outcomes for today’s students.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

Working Together: Two Models for Class Blogs

We initially introduced the sister class concept to our students as part of a larger pedagogical mission stated in both of our course syllabi:

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Academic inquiry takes place in a living, evolving, and interconnected world and, in order to be meaningful, it must engage with that world: looking around to understand what local environments can teach us, while listening carefully to what those outside our context can tell us. 4

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 3 But with the extraordinary flexibility of the blog form in terms of both subject and scope, finding specific parameters for our students’ writing was a challenge. 5 Dr. Hagood chose to take a relatively regimented approach that included a minimum number of posts and comments from each student. Working singly or in pairs, her seventeen pupils signed up to complete one weekly blog post covering any aspect of that week’s course material. Students could choose whether to write a “long” essay-like post of at least 500 words, or a shorter discussion-oriented post that included at least two carefully crafted questions for classmates to tackle. In the latter case, students were required to return to the post at the close of the week to synthesize their colleagues’ responses. Each student was also required to make a minimum number of comments, either on her own blog or on the sister class’s blog, over the course of the semester. Posts and comments were evaluated for completeness and punctuality only, leaving each student free to make her own decisions about the style and content of her work. Students were also encouraged to make additional posts as they saw fit, with any such post credited toward their comment count.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 The resulting discussion was both surprisingly sophisticated and surprisingly varied (see Writing the Natural State course blog). Students typically chose the longer format for their posts, and produced everything ranging from a lively critique of a film the class screened, to a debate about the social construction of the natural world, to a poignant reflection on searching for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. 6 Many also made excellent use of images, external links, and stylistic variations that gave their posts added interest and personality—a particularly impressive feat given that few in the class had ever previously engaged in any kind of web writing.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Click to read Rachel’s “Thinking of Brinkley and the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker” in a new tab/window. She makes great use of both images and links in her response to Hagood’s class viewing of Scott Crocker’s documentary film *Ghost Bird*.

Click to read Rachel’s “Thinking of Brinkley and the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker” in a new tab/window. She makes great use of both images and links in her response to Hagood’s class viewing of Scott Crocker’s documentary film *Ghost Bird*.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Rachel links to Brinkley’s city website to emphasize that fact that the town has always been dependent upon transportation infrastructure that primarily serves other cities. The website’s banner describes the town’s location as “Highway 40 between Memphis and Little Rock.” Click to read in new tab/window.

Rachel links to Brinkley’s city website to emphasize that fact that the town has always been dependent upon transportation infrastructure that primarily serves other cities. The website’s banner describes the town’s location as “Highway 40 between Memphis and Little Rock.” Click to read in new tab/window.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The commentary that emerged from these posts, and also in response to the sister class’s posts, was equally impressive. There were many instances of back-and-forth conversation between participants on several of the posts, suggesting that students were actively engaged in the intellectual interchange happening on the blog. Hagood also worked hard to integrate the blog with in-class discussion, both by highlighting especially interesting examples of student posts in class (and soliciting further comment from the group) and by adding her own comments to the blog when the conversation stalled or lost its way. Student assessments confirmed that blogging helped students to grasp and rearticulate new content, while giving them a greater sense of why their words matter. 7 One student observed that the blog “provided a different type of environment” in which “more people participated [and] everyone was able to think through their thoughts,” and another student explained:

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 The blog, in a sense, made me feel like I was contributing to something instead of operating within the school system: write a paper, paper graded, paper handed back and filed. This (course blog) is something that people, other people, could go on and see what this class was about, and how we, as individuals, think about certain issues. 8

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 5 On the other hand, Dr. Price’s model for the assignment, which varied significantly from Hagood’s, encouraged students to take greater ownership over the content and pacing of their blog by pursuing topics of their own interest as the occasion arose. At the beginning of the course, Price suggested that the class elect a webmaster who would design and maintain the blog throughout the semester, and set aside fifteen percent of the total course grade to account for participation in the blog (in lieu of a more traditional attendance/participation grade). The class then chose to set a minimum of ten blog entries per student for the semester, with the webmaster only required to complete five, and Price revised the syllabus accordingly. Halfway through the class, however, the students asked her if they could reduce this self-imposed minimum and, in the interest of nurturing their sense of autonomy over the project, she obliged. In contrast to Hagood’s guidelines, which confined students to a discussion of course readings for any given week, Price charged her students to write about any topics (relevant to the course) that provoked their interest, testing out the new sociological concepts and demographic skills they had learned against personal opinions, current events, and researched materials. In crafting their posts, they were encouraged to make use of data sets and other resources frequently drawn upon in sociological inquiry.

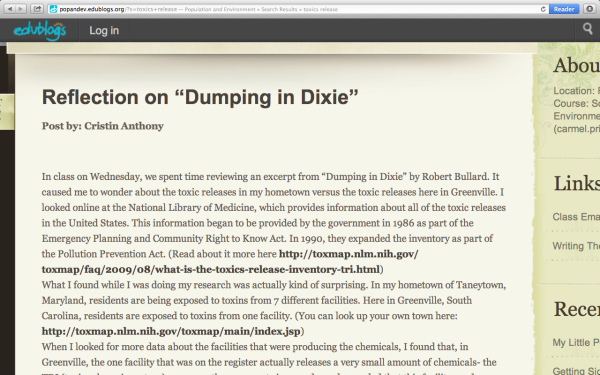

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 8 This arrangement allowed Price’s students to cover topics as varied as the social impact of farm-to-school programs, the media’s portrayal of human consumption and waste, and the FDA’s ban on blood donations from homosexual men (see Population and Environment course blog). 9 Even more importantly, it allowed them to explore these topics in a low-stakes, interactive environment in which they were free to experiment with new concepts and draw in outside sources; many of the posts are well-researched with a list of works cited. Because these posts were issue-focused, rather than referencing particular moments in class discussion, students in Hagood’s class felt much more at ease jumping into the conversation with their own comments and reflections. (Indeed, the majority of the intercampus blogging tended in this direction). In one instance, one of Hagood’s students even borrowed a resource discussed and linked on the sister class’s blog—the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory—to prepare a presentation about one of the class readings. 10

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

Click to read Cristin Anthony’s contribution to the “Population and Environment” class blog in a new tab/window. Cristin’s link to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, to search pollution sources in any part of the country, was later utilized by a student in Hagood’s class in a presentation about environmental justice concerns near Hendrix College.

Click to read Cristin Anthony’s contribution to the “Population and Environment” class blog in a new tab/window. Cristin’s link to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, to search pollution sources in any part of the country, was later utilized by a student in Hagood’s class in a presentation about environmental justice concerns near Hendrix College.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 5 At the semester’s end, we each felt that our class blogs had increased student engagement and enriched student learning, albeit in different ways. And while we both anticipated even more interaction between the class blogs than we actually found, the idea of sister classmates as a friendly but challenging audience was still a major motivating factor in our students’ writing. Our richest instances of interactive writing were, in the end, clustered around the teleconference meetings we had scheduled for the beginning, middle, and end of the semester, particularly as we found ways to use the blog as a tool to prepare our students for these discussions. In fact, the palpable excitement that can be detected in the blogs on and around the topics we discussed in teleconference—in passages either addressed to the sister class or merely referencing it to the home class—suggests that the telepresence of peers added an additional incentive for students to explore and experiment with course material. And although teleconferencing may not be appropriate for all class blogging situations, we did gain some useful insights in watching how it impacted our students’ performance. Our findings suggest that the “social presence” of other learners in digitally mediated environments is key to web writing’s power as a pedagogical tool. 11

¶ 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

The Next Step: From Learning to Teaching

As we first began to explore the idea of digitally linking our classes, we discovered a wonderful coincidence: we had both been deeply influenced by the work of the great turn-of-the-century preservationist, John Muir. Price had learned of Muir’s career, and his pivotal role in founding the Sierra Club, while doing conservation work in California. She was particularly fond of an inspiring passage in his 1908 essay “The Hetch Hetchy Valley”—calling for the city of San Francisco to suspend its plans to dam a canyon in the Yosemite National Park—in which Muir declares:

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul. This natural beauty-hunger is displayed in poor folks’ window-gardens made up of a few geranium slips in broken cups, as well as in the costly lily gardens of the rich, the thousands of spacious city parks and botanical gardens, and in our magnificent National parks. 12

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Hagood, on the other hand, had often used Muir in her classes to teach about literary Transcendentalism and its powerful effect on American visions of wilderness and nature. Building on our mutual enthusiasm, we planned an additional element for our classes that would bring our student writers face-to-face: a teleconference session in which we would discuss Muir’s essay, considering both the rhetorical techniques employed in his argument and the sociological context in which he wrote. This live conversation, we reasoned, would allow us to explore the issues considered in “Hetch Hetchy” from two disciplinary angles, as well as strengthen the bonds of trust between our students.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 1 At first, the value of this conversation—particularly in this new digital context—was difficult for our students to grasp. Price’s class, which was organized around the three primary components of population change (fertility, migration, and mortality), found the connection between Muir’s essay and their study of populations unclear, while Hagood’s students lacked the resources to delineate the social context that made Muir’s words meaningful beyond their powerful rhetoric. But this began to change as each class prepared for the meeting. Framing the Hetch Hetchy dam controversy in terms of population pressure from the growing city of San Francisco, Price had her students research census data from the turn of the century to share with their sister class. As they began to connect what they had learned about fertility with the rapid growth of the population in California, the question of whether to build the dam became a great deal more complex—and a great deal more debatable. Indeed, this was a turning point for the entire class as they began to realize that the demographic analysis skills they were learning could be connected to, and even shift their perceptions about, current and historic events, issues encountered in other courses, and even examples within their personal experiences. What’s more, in preparing and presenting their findings to Hagood’s class, they got the chance to practice and demonstrate their new research skills, proving to be very capable teachers in the process.

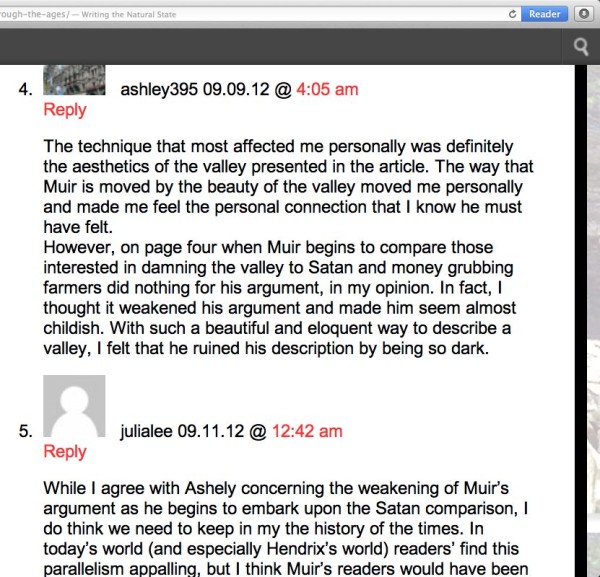

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Indeed the virtual discussion not only gave Hagood’s students a better sense for why the dam might have been needed—an argument which Muir only glancingly addresses in the essay—but also helped them to ask their own discipline-specific questions in much more nuanced ways. In a blog post responding to the teleconference, two of Hagood’s students noted that the strength of the essay lies in both the “rich, emotional imagery” that Muir employs to describe the Hetch Hetchy and the ruthless logic with which he attacks the opposition’s claims that damming the valley will create a lake roughly equivalent to the current landscape in beauty and recreational opportunity. Each type of argument has its strength, they note:

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 But, as the Furman class reminded us with their discussion of the demographic pressure of that era in the West, the intended audience was subject to a very different world-view than we have today. Which of Muir’s persuasive techniques do you think were most appropriate for his twentieth century audience? Which of these techniques was most effective for you? Is there a discrepancy between the two? 13

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 These questions, and the conversation that followed them, imply that with their sister class’s assistance, Hagood’s students were able to move beyond the fundamental question of how a text delivers its meaning and into higher levels of cultural analysis. Armed with the new perspective gained from their peers, they began to understand the important principle that words have different meanings in different contexts.

¶ 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

Members of Hagood’s class speculate about the impact of Muir’s religious rhetoric on his turn-of-the-century audience. Click to read original in a new tab/window.

Members of Hagood’s class speculate about the impact of Muir’s religious rhetoric on his turn-of-the-century audience. Click to read original in a new tab/window.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 One fascinating characteristic of the blogosphere, even on the small scale in which we worked, is that topics will continue to resonate through posts, comments, and links, even as they filter down to the unrecorded spaces of everyday classroom conversation. In just such a way, our early conversation about Muir and the Hetch Hetchy Valley continued to make an impact. Muir resurfaced in Price’s class during the unit on immigration, when the Sierra Club’s deeply divided position on U.S. immigration policy became a subject for discussion. Following the principles Muir drafted in such essays as “The Hetch Hetchy Valley,” the club has long favored public policies that protect the integrity of natural systems, which, given the important relationship between the physical environment and human population, has lead to much pressure on the Sierra Club to assume a stance on immigration. This debate provided Price an opportunity to take her class back to Muir’s essay, this time looking closely for rhetorical clues that help to shed some light on what Muir might have said about population and immigration issues. Using the literary analysis skills gleaned from their sister class, her students were able to complete this exercise, and to understand how Muir’s rhetoric continues to influence the Sierra Club immigration issue.

¶ 29

Leave a comment on paragraph 29 4

Conclusion

One of the most important things that our experiment in intercampus collaboration accomplished was to help our students integrate their learning into the broader field of digitally networked communication. This wired world extends to so many of the social spaces in which our students already move (and thrive), and in that sense it constitutes an important norm which we, as their teachers, ought to account for in our efforts to connect with and motivate them. Just as important, however, the idea of the network also powerfully shapes the demands of the business world and the practices of citizenship that our students will soon be called upon to fulfill. Teaching them to become responsible and valuable members of the learning community created by a class blog can play a small but significant part in preparing them for the challenges they will face after graduation, even as it creates a stimulating, supportive—and, dare we say, fun?—environment in which to learn. The relative freedom and extended range of web writing makes it a wonderful tool for helping students learn the fundamentals of any subject, and better still, to learn them together.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 2 As teachers, we were particularly gratified when one of Price’s students took the initiative to follow up on a comment made by one of her sister classmates in teleconference, to the effect that the city of San Francisco was now considering proposals to drain the Hetch Hethcy Valley (which, to Muir’s great despair, was dammed in 1923) and restore it to its former glory. From this snippet of information, the student turned to local and national newspapers to research the issue, and from these sources developed an impressive list of potential environmental and economic benefits and burdens that would result from the restoration. She then posted her list, with citations, on her class blog to encourage further debate. Though this student’s initiative might not be characteristic of all students—many of whom might not choose to put quite so much work into a low-stakes assignment—it does demonstrate the remarkable potential of class blogs to enhance and encourage student engagement and skill-building. And that potential alone makes them worth pursuing.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 About the authors: Amanda Hagood directs the Blended Learning Initiative of the Associated Colleges of the South. Carmel Price is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Furman University. They created the project described above while serving as Mellon Environmental Fellows at Hendrix College and Furman University respectively, 2011-2013.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Notes:

- ¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

- N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technologies (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), suggests that reading in digital environments—with their differing formats in line and paragraph length, their hyperlinks, and their capacity to display several texts concurrently—uses the brain’s formidable processing power in ways very different from the reading of print texts. Factor in the extraordinary amount of time today’s college students spend reading in such digital environments, and you have a generation which has been conditioned—both formally and informally—to read in a manner very different from traditional expectations for college students. ↩

- D. Randy Garrison, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer, “Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education,” The Internet and Higher Education 2:2-3 (2000): 95, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6. ↩

- Our project was generously supported by two Blended Teaching and Learning grants from the Associated Colleges of the South. For more information about the project, you may access our final reports on their Blended Learning Initiative webpage, Winter 2012, http://www.colleges.org/blended_learning/funded_proposals.html#w2012. ↩

- Joint statement in course syllabi by Amanda Hagood, “English 395: Writing the Natural State: Exploring the Literature and Landscapes of Arkansas,” Hendrix College, Fall 2012, http://naturalstate.edublogs.org/syllabus/; Carmel Price, “Sociology 222: Population and Environment,” Furman University, Fall 2012, http://popandev.edublogs.org/. ↩

- We chose Edublogs to host our class blogs because it provides generous storage space for course materials and media, easy-to-build pages that can be connected to the blog, and a wide range of page styles and widgets that can be incorporated into the blog for a truly pleasing appearance. Moreover, once we had created Edublog identities for each of our students, it was very simple for them to log in and contribute one another’s blogs. Another advantage of using this education-oriented blog service here is that it allows you to track the number of comments and posts made by each of your student users. ↩

- A particularly fine example of student writing is Rachel Thomas’s “Thinking about Brinkley and the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker,” Writing The Natural State course blog, August 31, 2012, http://naturalstate.edublogs.org/tag/ivory-billed-woodpecker/, which was especially meaningful for the many Arkansans in the class. The Ivory-Bill, which was long believed to be extinct, was allegedly sighted in the Big Woods of Arkansas in 2004, generating national attention for the state. See James Gorman, “Is Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Alive? A Debate Emerges,” The New York Times, March 16, 2006, sec. Science, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/16/science/16cnd-bird.html. ↩

- Hagood and Price conducted pre- and post-assessments to evaluate the unique components of their project; readers may access the assessments in their entirety through Hagood’s and Price’s respective final reports for their projects. ↩

- Anonymous student assessment, Writing the Natural State, Hendrix College, Fall 2012. ↩

- “Population and Environment” course blog, Furman University, http://popandev.edublogs.org/. ↩

- U.S. Department of Environmental Protection, “Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program,” http://www2.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program. ↩

- Garrison, “Critical Inquiry,” p. 89, believes that this “social presence”—which he defines as “the ability of participants in the Community of Inquiry to project their personal characteristics into the community, thereby presenting themselves to the other participants as ‘real people’”—is a key factor in the creation of successful online learning communities, along with the “cognitive presence” of individual students and the “teaching presence” of the instructor. ↩

- John Muir, “The Hetch Hetchy Valley,” Sierra Club Bulletin 6:4 (January 1908), http://www.sierraclub.org/ca/hetchhetchy/hetch_hetchy_muir_scb_1908.html. ↩

- “Persuasion Through the Ages,” Writing the Natural State course blog, September 6, 2012, http://naturalstate.edublogs.org/2012/09/06/persuasion-through-the-ages/. ↩

This seems a very appropriate first entry in the volume. I suddenly regret my strategy of reading through all the essays in reverse order (which I did in order to ensure that essays placed at the end got covered by readers, assuming that most people start at the beginning and proceed in a linear fashion).

This is a really strong essay. One of its successes is that it made me want to know more about what happened in those classes. That information isn’t necessary for the essay to achieve its goals; but is suggestive of its power.

This essay does a nice job presenting a specific case study and exploring the issues it raises. My main critique is about the introduction, which does not really focus on the core topic of cross-campus collaboration. I learned much more about that element than blogging, so I’d encourage a rewrite of the first few paragraphs to highlight the collaborative elements which are not introduced in this draft until paragraph 7, and downplay the blogging facet (which is really only one of the collaborative tools used).

Your essay, “Sister Classrooms,” has been accepted (with revisions) for the final draft of this volume. Several commenters praised your essay as an insightful case study, which could be even stronger with some revisions. Jason Mittell suggested reframing the introduction to focus on cross-campus collaboration rather than blogging, and Steve Safran and Barbara Rockenbach encouraged you to bring your strongest points to the surface. Kate Singer asked you to clarify if and how the class blogs helped students deal with or avoid discipline-specific jargon. See also several comments about linking the conclusion back to your introduction. Amanda’s response on how she inventively uses class time to highlight selected student blog writing, and how students wrote in different ways, also would be ideal to incorporate into the final draft if space permits. Finally, consider relating Carmel’s reflections on student privacy to the related essay in this volume by Dougherty.

The current draft word count is 4329 (as measured by WordPress), and the final version should not exceed 4000, so think carefully about making cuts as well as additions. The deadline for submitting your final draft is Thursday May 15th, though sooner is always better. This is a firm deadline, and if you do not meet it, we cannot guarantee that your essay will advance to the final volume. In the next few days, we will post further instructions on how to resubmit and edit your text in our PressBooks/WordPress platform.